`“Don’t underlook the Sixties… We did a lot of good stuff. But it shouldn’t shut you down from the moment.” ~ Wavy Gravy

“TURN AROUND,” the radio warned. “The New York Thruway is closed! If you’re heading to the Woodstock Festival, turn back. Now.”

I fiddled with the dial to find a scratchy station in Poughkeepsie.

“What should we do?” I asked my high school buddies, Rob and Joel. “What a mess.”

Our boyhood adventure lurched slowly toward “Three Days of Peace & Music,” but we now discovered that half of the nation’s youth were following the same lark.

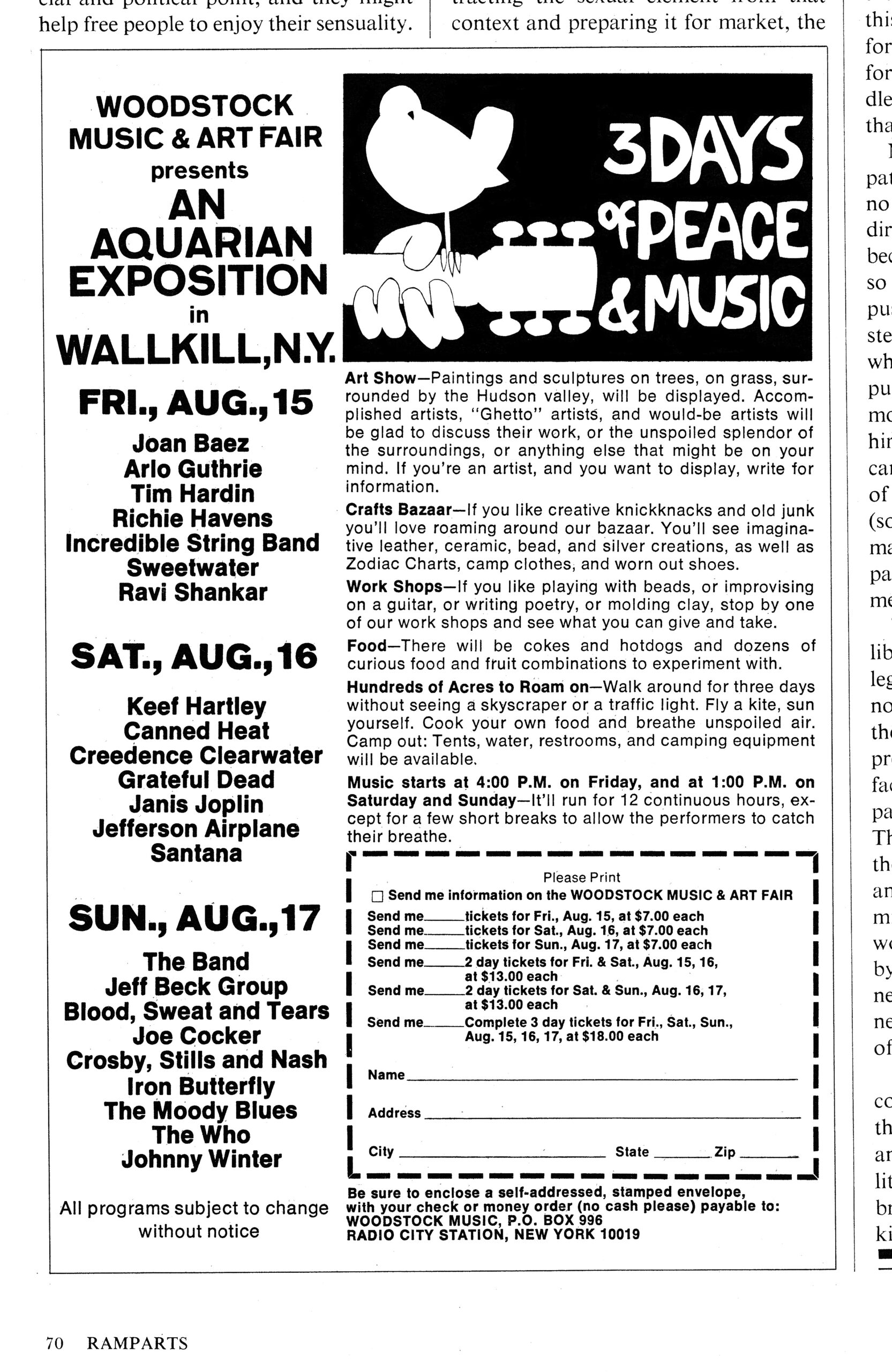

The organizers expected 50,000 aquarian concert-goers to commune near Wallkill, New York, but after the locals blocked the permit, the Woodstock Music and Art Fair made a last-minute move to a 300-acre alfalfa field near Bethel, NY. The idyllic weekend of music and art suddenly hemorrhaged into a half million people heading to a dairy farm owned by Max Yasgur, a Jewish Republican.

We had just graduated high school — our magical last summer of childhood — and while reading comics, spinning records, and snarking about life in general, Rob spotted a small ad in the back of Rolling Stone. Every great band short of The Beatles was in the line-up.

“We’re going,” Rob announced.

“Yes!” I seconded.

Our certitude was stunning — no deliberations, no considerations, no asking for permission. Somewhere in our Boomer firmware, the Woodstock subroutine had activated.

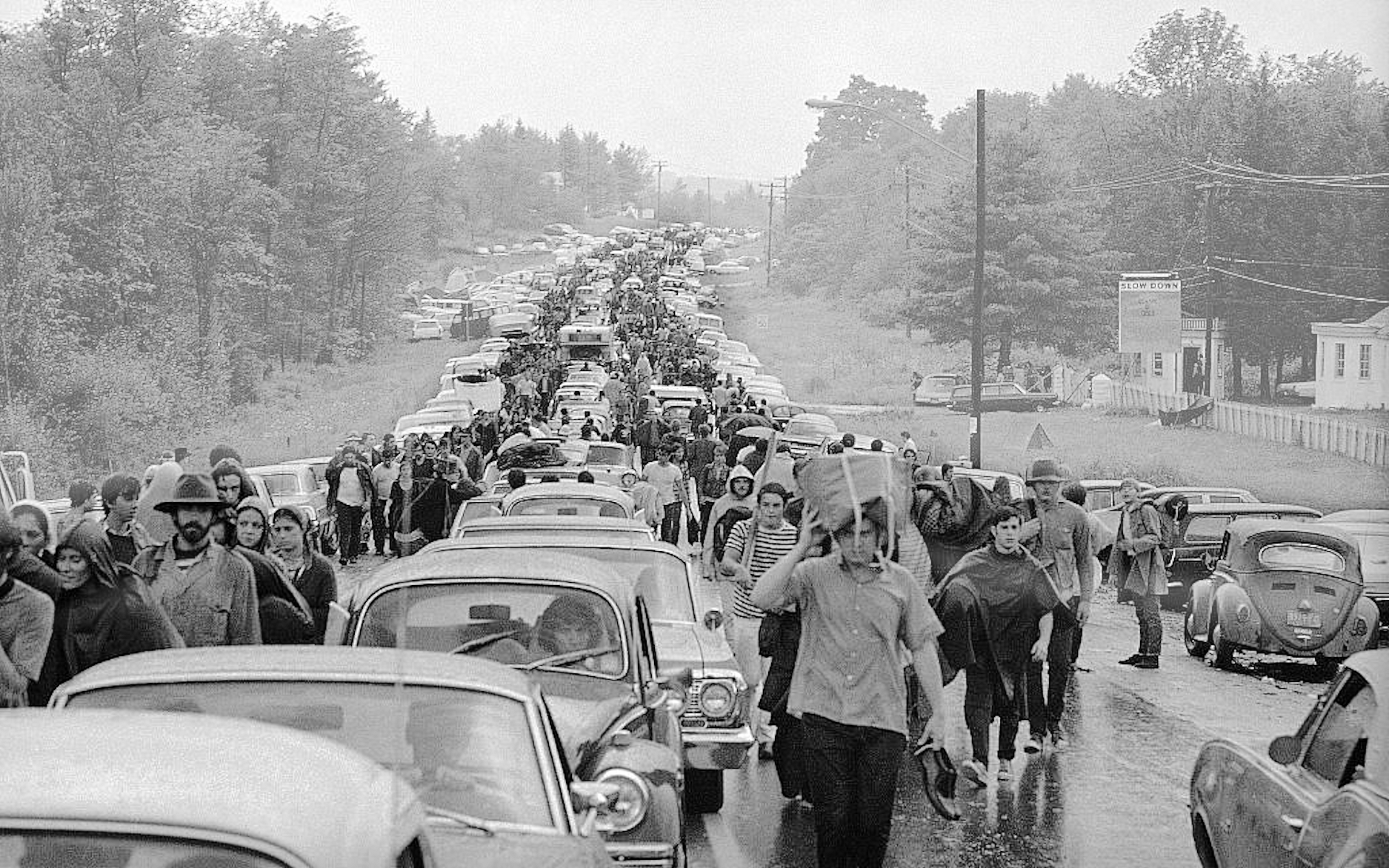

We borrowed Rob’s mom’s brand new Meadow-Green Olds Cutlass, swapped the back seat for a crib mattress, cranked up Crosby Stills & Nash, and embarked on a 13-hour road trip. As Chicago guys driving across the mid-section of New York state, we had the back-route advantage over the kids driving up from NY, Philly, and DC. Our fates merged on State Route 17 — a four-lane, 70 mph divided highway that hemmoraged into a bumper-to-bumper crawl of Beetles, hippie busses, and long-haired lemmings. Even the grassy shoulder and median had become a miles-long campsite. No planning could anticipate that a half-million kids would act on the same tribal impulse — and this was before the Internet.

“Let’s just turn around,” I moaned.

“We came all this way,” Joel urged.

We crept off the highway and devised a plan: As long as we could keep the car moving, we were good. Side roads, back roads, cow paths — our goal was to maintain forward motion. Finally, we hit a final impenetrable wall, pulled over, and walked. Granola bars hadn’t been invented yet, so like everyone else, we packed our oranges, filled our Boy Scout canteens, and walked.

A ten-mile stream of humanity swept us along like a biblical migration — iron filings pulled toward a lodestone of love. We cast our lot with the river of freaks, flower children, hippies, and wannabes — mile after mile of kids who had spent the last five years absorbing every riff of Hendrix, Who, Stills, and Nash, all longing to baptize their souls in the collective impulse. The dramatic universe was not yet an idea for me, but my being was quickly steeped in its epochal power and scale

Finally, the muck and mess of Woodstock emerged over the hill. Seeing the mud-soaked, sleep-deprived crowd camped under precarious light towers was unnerving. Every battle needs fresh troops, so we took our positions.

I won’t bore you with the performances, but the production values were rough. As the world’s first mega rock festival, The Who, Sly, and Santana still live in Rob and Joel’s memories. My pole star awoke when Wavy Gravy, the event’s announcer and clown impresario, took the stage:

“The Governor has just declared this a disaster area,” Wavy Gravy grinned with his goofy hoarseness.

Governor Rockefeller’s official proclamation set the dire tone for every story coming off the wire:

WHITE LAKE, UPI, August 16, 1969 — Tens of thousands of young music fans today began abandoning the muddy chaos of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair.

Advertised as three days of “peace and music,” the fair in this Catskill community has turned into a massive traffic jam in a giant mud puddle that has resulted in the death of one youth and the hospitalization of scores of others, many of them suffering adverse drug reactions.

Early today, promoters of the rock and folk music extravaganza, which had drawn an estimated 300,000 youths from throughout the United States, issued an emergency appeal for volunteer doctors and medical supplies to cope with the large number of sick.

Wavy Gravy took a dramatic pause, then giggled the sagacious punchline: “You know what I always say? There’s always a little bit of heaven in a disaster area.”

I didn’t know it then but know now: Wavy Gravy nailed it. The secret of Uplift lay hidden in the gumbo of mud, urine, and orange peels. A little bit of heaven held us together like a yin dot in a mud pit of yang. We shared our oranges, and the kids next to us shared theirs. This was my first taste of Uplift and its ability to distill a pint of heaven from a bucket of mud.

Fifty years later, I still wonder how 500,000 like-minded souls found their way to this improbable patch of land — home on any other weekend to Jersey, Guernsey, and Holstein cows.

For you social media geniuses, here’s your marketing assignment: Next August, attract half a million kids to an obscure farm in Sullivan County, NY. Make it happen without email, Twitter, SMS, radio, TV, Web, Facebook, or even fax. For difficulty, throw in a last-minute venue change, and for extra points, three days before the event, you must choose between erecting ticket stands and fences — or building a stage!

My Woodstock right of passage pales compared to what my parent’s generation faced on Omaha Beach, but each generational wave is different. Each is tasked to navigate the dramatic universe it encounters. Today’s kids face cyber wars, fake news, the end of democracy, and climate collapse — no small thing.

The universe is constantly in flux, but the drama continues its

spiraling story. My dad’s World War II experience reminds me how the basic themes in the dramatic universe keep re-emerging:

While working at GE as a Naval officer, Ed Miller helped develop the first sonar-guidance systems for torpedoes, a technology that sank 37 Axis submarines. One day, near the end of the war, my dad’s superior took him aside. “Ed, I’m going to show you the work we are conducting in a top-secret lab, but I need you sworn to absolute secrecy.”

My dad, expecting to see a death-ray in development, nodded yes. The supervisor unlocked the passage to a closed-off lab where, in direct violation of Roosevelt’s Defense Production Act, GE engineers were busy developing color television for the anticipated post-war consumer boom.

Yes, the Big Boom. I’m a product of that Boom, and from it, my peeps were charged to rip up the canvas and paint something new. I imagine every other generation gets a Boom inoculation during childhood. Gen X’ers were inoculated with Reagan (sorry) and Millennials with Obama. The Post-War Boom shot us out of the cannon into a Land of Plenty, and as a result, I grew up with Uplift hard-wired into my being.

Woodstock left an indelible impression that a cosmic pendulum swings from one generation to the next — from bust to boom to bust, and from Bob Hope to George Carlin to Sarah Cooper. The mysterious forces that summoned half a million hippies up State Route 17 are the same pendulum forces that move the planets. I can’t prove this in a lab because self-awareness is the only instrument that can penetrate the impenetrable.

After Woodstock, I spent the next half-century exploring self-awareness and the hard-wiring it rubs against in its search for inner freedom. Self-awareness can’t be activated like a light switch. It must be fermented and aged from crushed dreams. And like good wine, it elevates the experience of whatever tawdry menu your generation serves up.

J.G. Bennett, my philosophic mentor, described this awareness as the creative imagination – the ability to raise your vantage point above the world at hand and joyfully create the new. Music, art, poetry, architecture, and scientific breakthroughs all come from somewhere — but where?

J.G. Bennett explained:

There is this power of creative imagination that has all these properties: making doing possible, rejoicing before the Lord, giving the power to see through the inner eye, and working in all nature.”

Bennett makes it clear that the creative imagination is not God, but rather, a holy force that can become part of us. Were it not for our resistance, the creative imagination seeks to animate an inner freedom – what we experience as the creative act.

For artists and creatives, the creative imagination is the basic tool in the toolkit. For the student of Uplift who seeks to distill a pint of heaven from a bucket of life, the creative imagination opens the inner eye. It paints a road map to a better place.

Henry Corbin (1903 – 1978) took this power of the inner eye further in his exploration of The Creative Imagination of Ibn’ Arabi:

Between the universe that can be apprehended by pure intellectual perception and the universe perceptible to the senses, there is an intermediate world, the world of Idea-Images, of archetypal figures, of subtle substances, of ‘immaterial matter.’ This world is as real and objective, as consistent and subsistent as the intelligible and sensible worlds; it is an intermediate universe where the spiritual takes body and the body becomes spiritual… The organ of this universe is the active imagination.

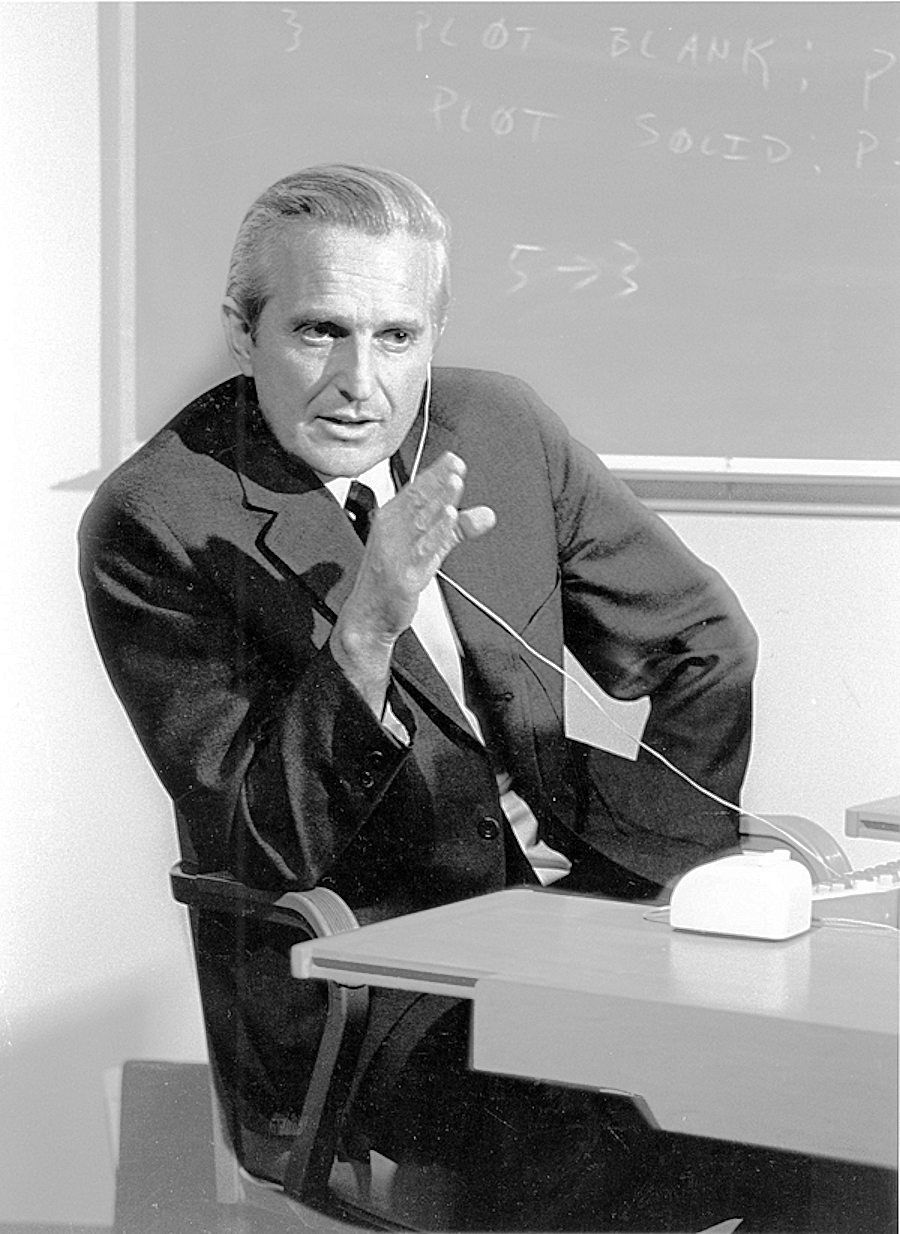

When I think of the creative imagination – the archetypal world that lives between intellect and sense perception – one name comes to mind: Doug Engelbart, the father of desktop computing. Doug had an epiphany in 1950 that changed the world. In a single creative flash, a complete vision of the information age appeared to him. This vision became the basis for the Internet and the modern personal computer, including, in 1968, the handheld mouse.

Doug Engelbart demonstrated how the future comes into the present, not step-by-step, but like a birth from a higher world and through game-changing leaps from the creative imagination. From The Guardian:

Next time you drag a document across your desktop and put it in a folder, spare a thought for acid. Organizing your files might not seem like a psychedelic experience now, but in 1968, when Douglas Engelbart first demonstrated a futuristic world of windows, hypertext links, and video conferencing to a rapt audience in San Francisco, they must have thought they were tripping. Especially because he was summoning this dark magic onto a big screen using a strange rounded controller on the end of a wire, which he called his mouse. Like many California tech visionaries of the time, Engelbart was an enthusiastic advocate for the mind-expanding benefits of LSD. As head of the Augmented Human Intellect Research Center at the Stanford Research Institute, he and his team would drop acid under test conditions in the hope of inspiring new breakthroughs.

Unlike the computer engineers at Stanford, I didn’t drop acid at Woodstock. But, one month after sensing myself as a yin dot in a sea of mud, my creative imagination awakened again — this time as a freshman at the University of Illinois, 1969.

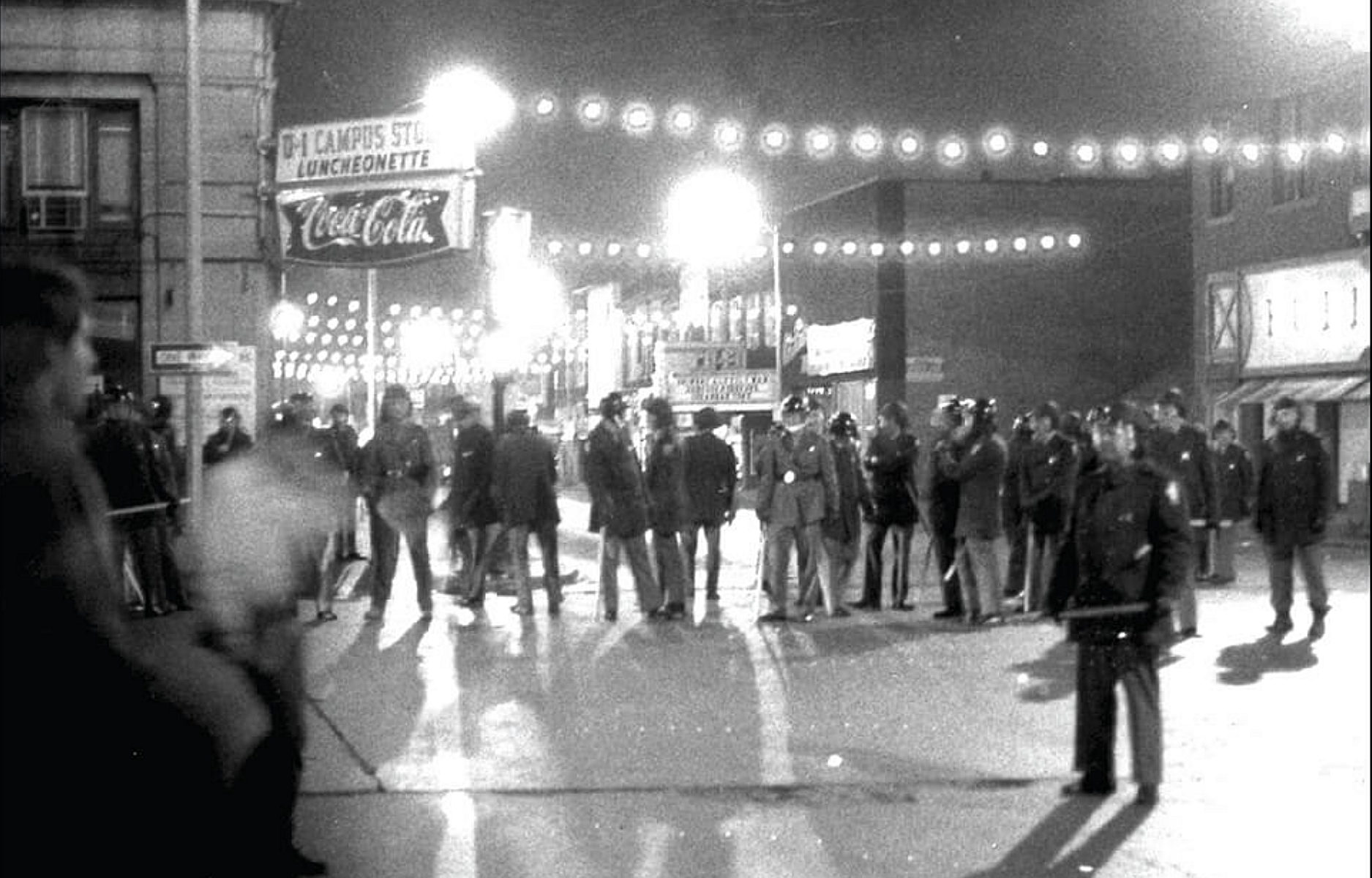

College life thrust me into a potent brew of political chaos. I grew up in a leafy suburb, so watching the geopolitical forces erupt on my campus came as a shock. A few weeks after unpacking my suitcases, we chartered busses to the Vietnam Moratorium in Washington, DC, to be hazed with tear gas. Upon return, the school was disrupted by a convulsive series of events — a student strike, fire bombings of the police station, recruiting station, ROTC, and Lincoln Hall, followed by the inaugural Earth Day, and a speech by Dr. Benjamin Spock reminding us that the Declaration of Independence entitles people to a revolution. Next came the disheartening discovery that our school’s namesake Illiac IV — the fastest computer in the world — was secretly funded by the Department of Defense. Topping it off, the National Guard fired 67 rounds in 13 seconds into a crowd of fellow Midwestern students at Kent State.

There was more. As a harbinger of Black Lives Matter, on the morning of April 29, 1970, a local cop fatally shot 23-year-old Edgar Hoults near his home. Hoults, a security guard at Follett’s, our campus bookstore, had been unable to sleep one night, so he went to the store to help his co-workers while his 21-year-old pregnant wife, Alice, slept with their two small children. Hearing commotion, Alice looked out her front window and saw nothing. Suddenly, she heard a gunshot at the rear. She opened her back door to see her husband face down, bleeding in the grass. Her neighbors had to restrain Alice, shaking and crying as her husband was lifted into an ambulance. Alice never saw Edgar again until his body was presented at the funeral home. No police officers or city officials

explained to her what happened.

At the trial, cops claimed that Edgar had been pulled over behind the bookstore, fled by car, crashed, and was chased to the field behind his apartment. They did not offer a reason why Edgar fled. The officer said his service weapon went off accidentally when he slipped on wet grass (while scoring a perfect bullseye to the back of Edgar’s head). Adding to the terrible, horrible irony, Edgar was working late at Follett’s to clean up firebomb damage from the students.

Pumping up the crazy, the school trustees, in their infinite wisdom, disinvited Chicago Seven defense attorney William Kunstler from speaking on campus. I was in the crowd of 2000 students waiting to hear Kunstler speak, and — crowds doing what crowds do — we “decided” to march toward the President’s mansion, but we first made a strategic detour through Dormitory Row to gather troops.

Imagine hanging in your dorm, spinning records, and suddenly hearing a raucous protest from the street below. One after another, stereo speakers popped out of dorm windows, blasting the Rolling Stones. The crowd’s roar of angry epithets mixed with Jagger’s lyrics to paint a dark, dystopian scene. “Hey!” Jagger yelled, his voice ricocheting off multiple buildings, “Think the time is right for a palace revolution!”

Instantly, the march grew to 4500 students. As we neared the President’s mansion, the cops formed a barrier — not campus cops — but the fearsome, sadistic State cops with their four-foot clubs. A row of meek National Guardsmen stood to the side with their military jeeps lined for battle. Who were these Guard guys, 18 and 19 years old? They looked like the guys in my high school locker room, but now with different helmets, different uniforms, and loaded M1 rifles. One guy even had a double-tank flame thrower strapped to his back in case a rice paddy needed immolation on the campus quad.

“Sorry guys,” I snarked, “All we got are cornfields.”

And me, I just wanted to hear Kunstler.

The frolic of protest quickly morphed into menace, ratcheting up the anger and fear. Wavy Gravy could have diffused the “seriousness of it all,” but he wasn’t there. I was there. And then, my active imagination took hold. Maybe I was Arjuna, taking Krishna’s counsel on the battlefield. I became very still inside – a yin dot in the sea of anger. Hippies and cops, cops and hippies — each performing a desperate kabuki, one side creating the other. The universe had a score to settle that night — maybe Mars got too close to Jupiter, and this cosmic slight rippled to Earth in performative response — like an imagined opera, “The Fight of the Illini.” Strangely, Bruce’s Arjuna-feeling body didn’t know how to respond.

“I don’t feel anger. Shouldn’t I be angry?”

Without Krishna telling me what to do, I felt confused. “Everyone else is angry. Does a protester have to feel anger? Does a falling tree have to make a sound? Am I just the witness? The yin dot in a sea of violence? Does a point of stillness pen the script for the dramatic universe?

The escalating threat of cop violence became too much, thinning the crowd. Some hardcore comrades continued toward Follett’s Bookstore to break more windows — oblivious to the fate of Edgar Hoults.

I retreated from this modern-day Mahabharata and stumbled back to my dorm room. I couldn’t read the Sanskrit of confrontation, but my inner eye saw how bigger forces enlarged my present moment:

From JFK to LBJ, Gulf of Tonkin, Dien Bien Phu, Ho Chi Minh, Ngo Dinh Diem, Nguyen Cao Kỳ, to Nixon, Kent State, and even to Edgar Hoults. Each player hit their marks and performed their scene. But like the kids breaking windows, no one had the full script in hand. That’s the thing with extras. Hitchcock would have calmly directed, “Take your rocks. Now throw! Cut! Thank you. You can leave.”

Nguyen Cao Kỳ was more than a bit player in this story. As the leader of the Republic of Vietnam, he had a bigger role. When Shakespeare penned “All the world’s a stage,” the Bard would have anticipated the flamboyant Nguyen Cao Kỳ, with his dashing flyboy charm, tailored suits, glamorous wife, and silky corruption.

Sudden reversals of fortune signal the plot points of the dramatic universe. After nineteen years of conflict, the Vietnam War collapsed in a single day — on April 30, 1975. If you’ve been keeping track, the sequel returned 46 years later when America’s 20-year Afghan War collapsed in a single week. And for the prequel, in 1842, British troops were forced to retreat from Kabul during the First Anglo-Afghan War. Of the 16,000 British soldiers and civilians guaranteed safe passage to their garrison in Jalalabad by Afghan tribesmen in 1842, only one European made it to safety. The rest were massacred or died of exposure.

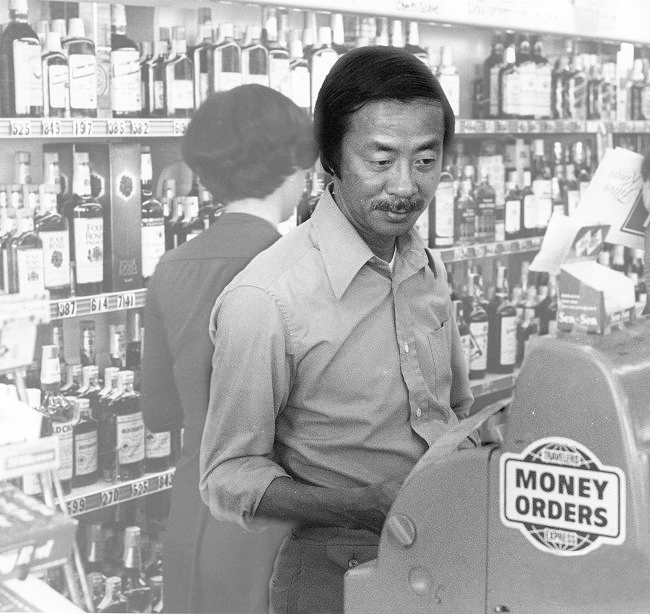

During Vietnam’s collapse, the nation’s first couple, Nguyen and Madame Kỳ, were rescued by helicopter atop the U.S. embassy and fled to the United States, where they adopted their new all-American roles: running a liquor-deli convenience store a few miles from Disneyland. That’s right. After our nation shoveled 60,000 American lives and a trillion current dollars to prop up a geopolitical sinkhole, the tragic irony of the dramatic universe showed its hand. South Vietnam’s flash-in-the-pan leader, a playboy partial to purple scarves, upscale nightclubs, and beautiful women, was now selling booze by the pint, beef jerky, and Hustler magazines over the counter in a derelict neighborhood in Garden Grove, CA. This scene became indelibly etched in my consciousness. Toto had pulled back the curtain to reveal the Great and Powerful Oz – a mere humbug.

After days of student protests, the Great and Powerful Trustees invited William Kunstler back to campus, this time to a crowd three times larger than the first. The dramatic arc of apparent chaos etched into my being. I saw how the present moment stretches, and how the inherent irony – the truth of the story – is revealed. Whether that truth is greed, hypocrisy, meanness, or weirdness, irony shows its hand through opposites.

Consider the 43rd President: After sending thousands of troops to death and disfigurement for an immoral war, George W. Bush chose a compulsive new hobby for his golden years – painting portraits of dogs and cats, still-lifes, landscapes, two self-portraits en toilette, and a collection of portraits of veterans. I don’t want to psychoanalyze, but his integration journey would have been better-served painting portraits of the 151,000 Iraqi civilians who died from the war or those captured and tortured at the hands of the CIA.

Nguyen Cao Kỳ shape-shifted to reveal his own ironic truth. After his liquor store failed, he tried the seafood business. This also went bankrupt. To cap the couple’s legacy, his wife attempted suicide at the luxurious Manila Hotel. I don’t feel sorry for grifters. You have two choices in life – ride the pendulum or get hit by it. You can’t outwit it.

Like Kỳ, the Woodstock promoters learned how sudden reversals of fortune signal plot points in the dramatic universe. When the pendulum swung — collapsing their Woodstock business dream — they didn’t panic or try to protect their losses. Instead, they let Reality play out in real time: they opened the gates to the hippie hordes. The promoter, Michael Lang, remembered:

“We wanted to ensure that anybody who came to our event was welcomed. Of course, in the original plan, we had gates and ticket booths… The counterculture was heading to an event run by their own. We just avoided the silly confrontations that stupid rules can create.”

Lang put a hippie spin on his reversal of fortune. The suddenly free festival left him and his partners with $1.3 million in debt (a $9 million loss in today’s dollars), but the pendulum of risk swung again. They made it all back from album and movie ticket sales.

History textbooks don’t focus on pendulum swings; they teach

history as a string of discrete events because that’s how books are written: one chapter after another. J.G. Bennett’s four-volume magnum opus, The Dramatic Universe, saw all of history as a single dynamic story guided by a demiurgic intelligence. If the universe is indeed dramatic, some being must write, cast, and direct the play. This intelligence has traditionally been called the Demiurge — from the ancient Greek, Dēmiourgos, the Craftsman. If God is the Boss, the Demiurge is “God’s fixers.”

Defined as “a being responsible for the creation of the universe,” the Demiurge is neither an absolute God moving the pieces nor the random-chance mechanics of subatomic particles. Bennett defined Demiurge as a “mode of Being associated with intelligence higher than human and with a far greater Present Moment.” In this way, the Demiurge works on a bigger stage than our day-to-day lives can take in.

Bennett explained to his students, when “I use the word Demiurge, I mean the same as the writers of Genesis meant when they used the word Elohim.”

In Genesis, Elohim (God) is both the He who created heaven and earth and the Us who created man in “our” image. In Psalm 8:5, Elohim is also translated as angels.

Is the Creator a He, an Us, or the Angels? Take your pick, but I’m sticking with the Demiurge as the Creative Imagination that fashions our world. In this way, the dramatic universe plays out as the higher mirror of our impulses — a conscious intelligence stumbling through a game board of chance, making it up as it goes along. The emergence of life, the appearance and disappearance of species, the rise and fall of civilizations, and the redemptive arc of human history are inseparable from the demiurgic angels who help us find a parking space — or even the psychedelic spark that imagined a new species of mouse. Thank you, Doug Englebart.

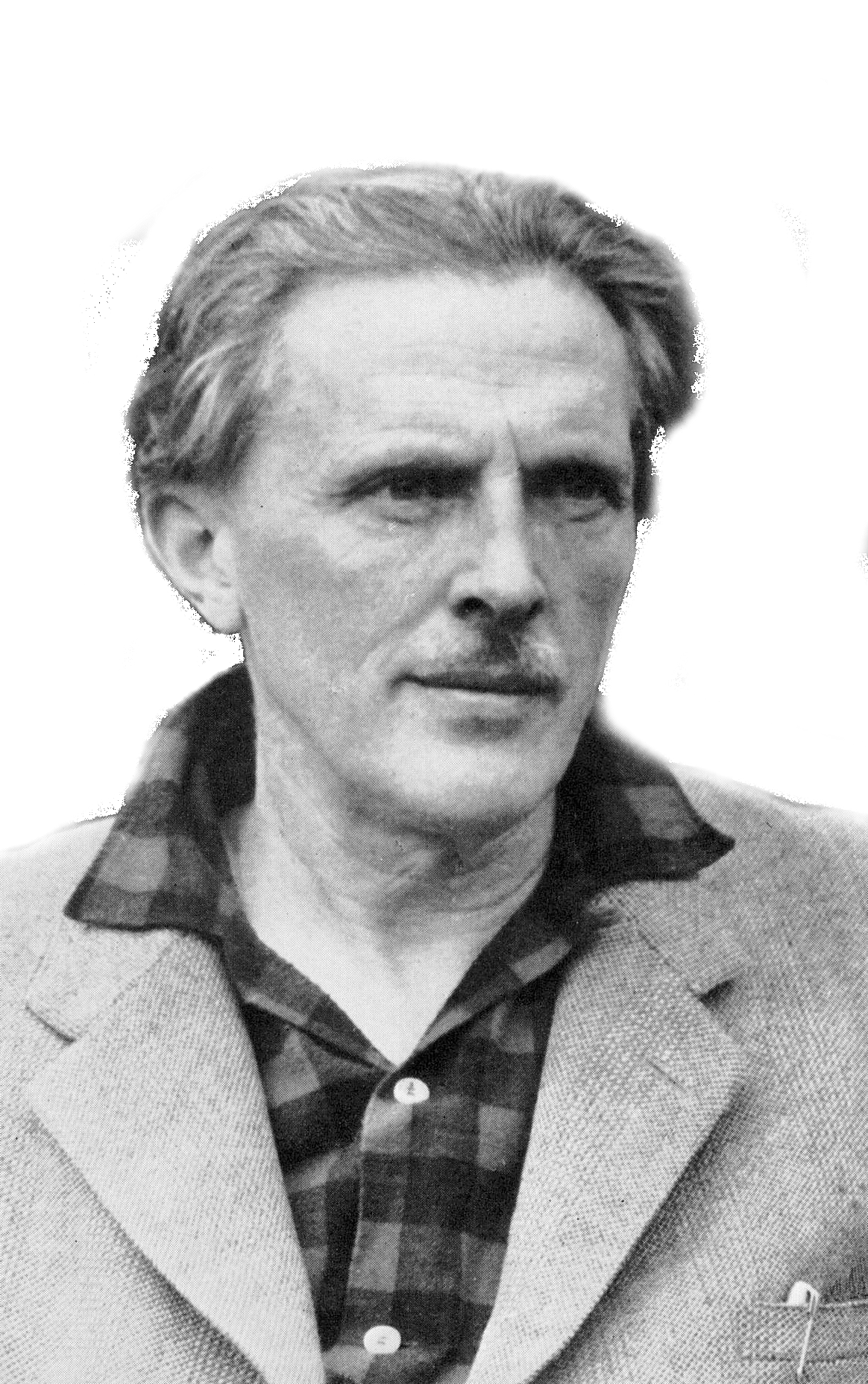

J.G. Bennett (1897 – 1974) was a British scientist, technologist, metaphysical teacher, and author. During World War I, he was blown off his motorcycle by an exploding shell, then taken to a military hospital where he remained in a coma for six days. This precipitated an out-of-body experience that launched his lifelong inquiry into the deeper reality.

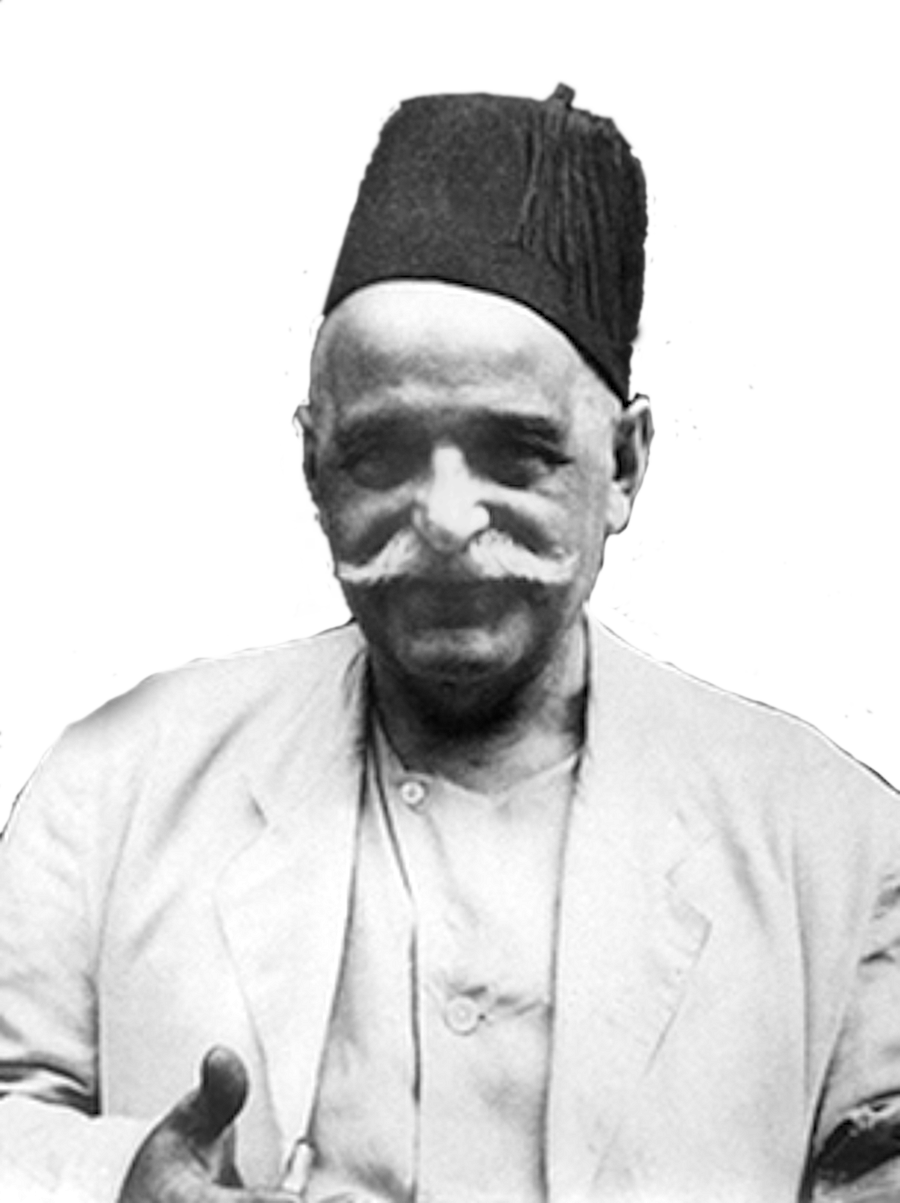

In 1923, Bennett met the Russian philosopher and mystic, G.I. Gurdjieff, who introduced him to the esoteric workings of the universe and the techniques that could transform humanity.

Bennett melded Gurdjieff’s metaphysics with the discipline of his scientific life. As a unified vision of reality, The Dramatic Universe challenged the reader from the first page. One commenter warned, “In reading it, you feel as though you need a Ph.D. in history, physics, philosophy, chemistry, and biology. Being able to speak Latin and French would also be useful, as he’ll often use those languages without translation.”

Anthony Blake, Bennett’s editor and protege, wrote in 1976:

The publication of The Dramatic Universe was one of the major intellectual events of this century and, in keeping with all major events, passed almost unnoticed by the world at large… Bennett had set himself to give a framework for understanding the whole of human experience.

Whether it’s a unified field theory or a Web conspiracy, it’s human nature to seek a theory of everything — a finishing puzzle piece to explain the complexities of life. Everything can’t fit into a theory, nor should it. It’s a noble task, and this book follows that quixotic spirit — to find a unified understanding of Uplift.

Unlike Bennett’s masterwork, my question has been more humble and childlike. I asked it on page one: “Where is the Uplift?” If we’re released into life like a glider pilot flying on a cushion of air, gravity slowly, then suddenly pulls us to our fate. How does the leader of the free world end up painting still-lifes and pets? How does the Premier of the Republic of Vietnam become a humbug selling pint liquor for his second act?

Experienced glider pilots know where to find the next Uplift — the column of rising warm air that lifts the glider to continue the journey. In this way, Uplift holds the secret to continuous renewal.

Uplift provides an anti-gravity force for continuous renewal like a hot air balloon releasing its ballast to chart new horizons. This periodic flush-cycle of mental ballast extends the range and enlarges the map. It expands the present moment — the place of pure action and freedom that is not constrained by the past nor crippled by anticipation of the future.

When Bennett devoted his final volume of the Dramatic Universe to the history of the human mind, he sought a stage large enough to cast his story. He enlisted the present moment:

All experience is contained within the present moment. This is the only immediate and irreducible certainty. The present moment is not a dimensionless point but a finite region of experience that never changes inasmuch as it is always present and yet always changes inasmuch as it is in a state of flux.

Bennett’s present moment was not the linear sequence of Kunstler, dormitories, cops with clubs, and broken windows. Bennett defined the present as the content of human experience — the total immediate experience.

Think of the universe as a big TV with 8 billion streaming channels (including your own) – channels that flip from retro to romance and from hell to healing. In this larger present moment, those channels constitute one big show, a timeless redemptive drama where Indochina’s corrupt colonial history juxtaposes with protests at a corn belt university.

Unlike physics which measures the dimensions of space and time, Bennett’s present moment is bounded by the dimensions of human experience — through autonomic, sensory, and conscious awareness.

My teacher, Bhagwan Awatramani, narrowed it further when he

explained to me: “The present is not a moment.” In Bhagwan’s explanation, the present is not a moment; it is outside of time. When I kissed Karen in the elevator to seed the book in your hands, the creative imagination spawned it whole even though it would take over a year of hard work for time to catch up with that present moment.

I remember watching This is Your Life as a child— possibly the first “reality” TV show. The host, Ralph Edwards, surprised guests in front of a live audience by reciting the story of their lives. Long lost colleagues, friends, and family would step out from behind the curtain while Edwards narrated the guest’s life story. The U.S. Army spawned the idea for the show when they asked Edwards for help rehabilitating injured soldiers. The Army felt Ralph Edwards could help war-stressed soldiers integrate the stories of their lives. The surprised guests who burst in tears offered more than vicarious entertainment. They illustrated the “expanded present moment” and how gratitude and redemption emerge when time catches up for Ralph Edwards to declare, “This is Your Life.”

Consider a very different present moment in the dramatic universe — the storming of the Capitol on January 6, 2021. The nation shuddered for six violent hours – from 2 pm when the Electoral College count was halted until 8 pm when the Senate resumed. Instead of six hours, you can enlarge that moment to the two months of attempts to illegally overturn the election — from November 3 to January 6 — or the eight months of false assertions that voting by mail constituted fraud.

Expanding the present further, the Capitol insurrection was also telegraphed four years earlier when Trump oddly inserted “American carnage” into his inaugural address (followed by Kellyanne Conway “throwing some mean punches” at the Inaugural Ball).

“American carnage?” I pondered, “What the hell is he talking about?”

When Trump spoke those words at his inaugural, my present

moment expanded, and not in a good way. Just two weeks earlier, Barack and Michelle Obama had joyously hosted the cast of Hamilton in the East Room — and now, boom, Trump changed the channel to carnage. Years before the storming of the Capitol, Trump’s foreboding fetish with violence foretold what was to come with Charlottesville, Portland,

Lafayette Square, and the attack on the Capitol.

The four Trump years was not the launch of a new era. Author Anand Giridharadas described it as a convulsive backlash against the future – a temporary recoil against the storyline of the dramatic universe:

[The Trump era] is not the engine of history. It is the revolt against the engine of history… We are living through a revolt against the future. The future will prevail.

Whether we face a future of carnage or caring, it is not out of our hands. The Greek philosopher, Heraclitus, said, “Character is destiny.” In this way, the insurrection played out as the imprint of character captured in the seed impulse — Trump’s obsession with carnage.

A seed impulse can also be called will. Will is not complicated, but it is also sacred. The entire Quran is said to exist in the opening Bismillah — that in its authorship, the sacred text manifested when the quill touched the parchment. Be, and it is. From the Quran:

He is the One Who has originated the heavens and the earth, and when He wills to (originate) a thing, He only says to it: ‘Be,’ and it becomes. 2:117

In Arabic, the imperative verb for Be is Kun. Kun fa-yakūnu — Be, and it is.

His command (of creation) is only that when He intends (to

create) something, He says to it: ‘Be,’ so it instantly becomes. 36:82

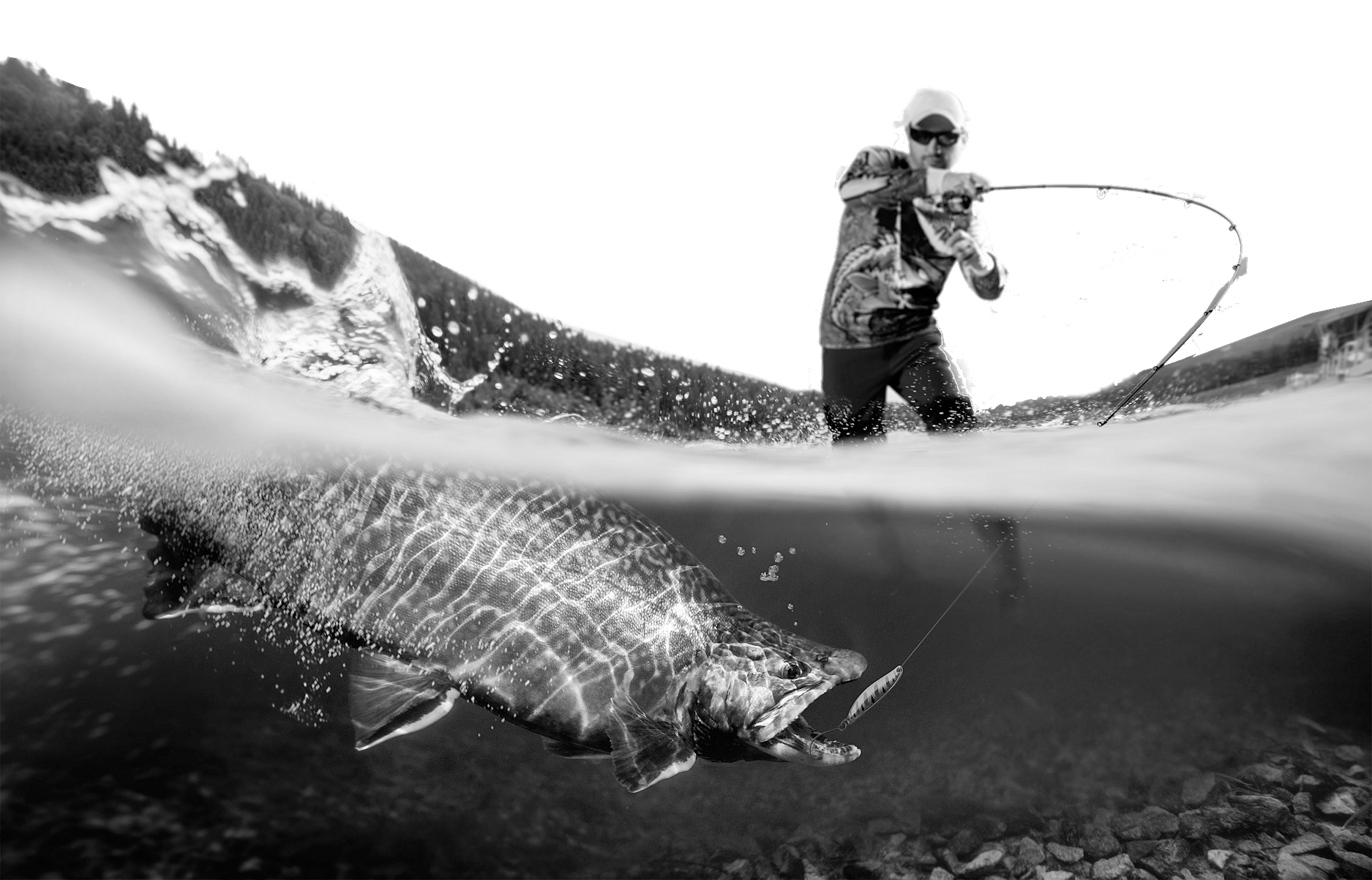

We experience God’s command, Kun, through the action of Will — not my will or God’s will, but simple, non-complicated will. Will sees the play while moving it forward. Will is the driving force for Uplift. As the actors of our stories, we embody this Will. Whether we sit in meditation, place a quill to a parchment, or go fishing, the present moment enters the action through Will — the perfect cast (Kun) that lands a trout.

This is the creative imagination in action — Engelbart envisioned the information age, Trump willed a coup d’etat, and I saw the span of history on my violent college street. Instead of “I’m hot, and my feet hurt walking to this muddy music festival,” the creative imagination senses the larger present moment, “The times, they are a-changing.”

Will witnesses the dramatic universe in a transformative arc – the half-century that connects Edgar Hoults (d.1969), to George Floyd (d.2020). One died in obscurity, and the other convulsed the nation and the world for weeks of protest. It would take 50 years for the nation’s majority to become “woke” to “Black Lives Matter.” As Edgar lay in a pool of blood after working the night shift at Follett’s, a sounding note was struck – a dark chord that ultimately summoned a national movement and renamed the avenue in front of the White House, “Black Lives Matter Plaza.”

My present moment stretched that night in Champaign, Illinois. I didn’t recognize the full irony of my school’s decision to bar William Moses Kunstler, a lawyer who gave a lifetime of work to the principle of equal justice under law. Kunstler stretched the American present moment in his unpopular defense of Communist revolutionaries, the Freedom Riders, the American Indian Movement, Black Panthers, Attica Prison rioters, a string of notorious mobsters, and, at the time of his death, the Blind Sheik, Omar Abdel-Rahman, for his role in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. He was also a special trial counsel to Martin Luther King Jr. True to form, Kunstler claimed he was headed to the airport to represent Lee Harvey Oswald on the morning Jack Ruby gunned Oswald down in Dallas.

In my hometown, Chicago, Kunstler put Allen Ginsberg on the stand to chant “Om.” He also defended two cases of flag burning before the Supreme Court. Always ahead of his time, Kunstler understood the exercise of Will. He described himself as a “legal performance artist.” He understood that “you always want to be in the media, no matter what gets you there.”

Kunstler’s final role as the nation’s moral performance artist would have to wait thirty-five years after his death. The 2020 movie, The Trial of the Chicago 7 put a mirror to the Trumpian moment. In 1969, the government staged a show trial to send seven random white peace activists (plus Black Panther, Bobby Seale) to prison for a decade for protesting the Vietnam War in Chicago’s Grant Park. In 2020, for the crime of protesting unwarranted police killings, the federal government conscripted a faux military from various agencies to stage “show riots” in downtown Portland and Lafayette Square with the cynical intent to foment riot footage to promote the Trump campaign.

From Grant Park 1968 to Lafayette Square 2020, life unfurls in a circular motion. We experience the circular rhythms of day and night, the four seasons, and our revolution around the sun. Life also spirals — spiraling up as growth and spiraling down as decay. Political promises spiral down while pole beans planted by urban pioneers in abandoned city lots spiral up.

Time marches forward – often like a needle stuck in an LP groove. Continuous renewal coaxes Uplift from these grooves. Glider pilots catch thermals and follow the updraft in a spiral flight path. We don’t have wings to catch an Uplift, but we have an active imagination that can jettison mental ballast and re-imagine our possibilities.

When I was three years old, lying in bed one night and unable to sleep, my creative imagination took a strange turn. Like an ever-rising drone shot, I saw my immediate world — people going to work, politicians on TV, and everyone worrying about money — all out of sync with our true circumstance as a floating speck in space. As the drone pulled up, I saw cities and forests, mountains and oceans. I also saw other lands with different customs and cultures. As I continued to pull up and away, I saw planet earth hanging in space. Apollo hadn’t taken our selfie yet, but I imagined what it would look like. And then I got scared.

I hadn’t heeded the advice of poet, Nick Flynn:

Children under, say, ten, shouldn’t know that

the universe is ever-expanding, inexorably pushing

into the vacuum, galaxies swallowed by galaxies,

whole solar systems collapsing, all of it

acted out in silence.

Yep, I was under ten and wondering, “What’s outside our solar system? And what’s outside of that? Where exactly are we?” This vast gap between our tedious, goofball lives and the majestic reaches of space made no sense. Hitchcock should have yelled, “Cut!” and summoned the script girl to explain the continuity gap to me. Even at that young age, I sensed a dramatic story at play, that humanity performs in a “theater of the absurd” — the present moment.

Feeling freaked, I shuffled my pajama feet down the hall.

“Mommy, I can’t sleep.”

“That’s okay,” my mom reassured. “It’s okay just to rest.”

And that is where I am, writing this oddly non-linear chapter on my initiation into the dramatic universe on the morning of our first COVID Christmas. (I know the Capitol insurrection is 12 days away, but I bop around as I write). You probably have a vivid memory of this particular Christmas. Someone you love may have been sick or even passed away. Maybe you opened presents with your hygienic family pod around the tree. I’m preparing for an antiseptic family Zoom. Either way, the dramatic universe changed your holiday plans.

My “holiday” message is to fire up your creative imagination and stretch the present moment of all your Christmas memories until the pieces of your story fit together, your heart feels safe, and you know you’re loved. Like the message a previous generation learned from Ralph Edwards: if you embrace the larger present moment, it returns the favor by remembering you in love.

As I fumble with the kettle and prepare for an empty-nester holiday, I look out our frosty cabin window and realize that Santa has delivered the rarest of gifts — a winter wonderland of white fluffy Christmas snow in the Deep South. Maybe the dramatic universe still has some Uplift up its sleeve.

REVIEWS: Rumi Comes to America

“This book tells the story of one of the most important moments in America’s recent religious and spiritual history using accounts of those involved and new translations of audio recordings from the time. Written with honesty, compassion, and understanding, it beautifully conveys the feeling of the place and period.”

Mark Sedgwick,

Department of the Study of Religion,

Aarhus University, and author of Western Sufism: From the Abbasids to the New Age (Oxford University Press)

“Bruce, thank you for doing this good work!”

Coleman Barks, The Essential Rumi

“The book is a treasure for us… Such a joy to hear the story of that time. It is so wonderful to hear the words he said at that time and connect them with what has grown in me since.”

Kim Payton Ph.D.

REVIEWS: FORTUNE

“This is a riveting tale of risk, spiritual teachers and con-men, self-discovery, love, and healing, written with humor. I shared the paradox of studies with Reshad Feild, and applaud the honesty of this account, both the inspired teaching and the seamy underside. What a voyage, from razzle-dazzle California through stage 4 cancer, “following the bread crumbs” of Hazard and riding the Octave. Bruce shares his path to trusting and accepting what happens, while staying alert and without effort. Hurray for Karen, her buoyancy, and her heroic response to cancer. Bravo, Bruce, for being yourself and sharing it with us. He describes himself as “a consciousness guinea pig.” What is shared is real spiritual experience that includes the stumbles, doubts, and crises, with self-deprecating humor, and it is priceless.” – Subhana Ansari

“Fortune: Our Deep Dive…” is a must read for anyone on a journey of spiritual exploration. Weaving together traditions through the lens of life challenges and changes, Bruce takes us along on his quest for understanding the mechanics of chance, success, and enlightenment, bringing us to the point of understanding and acceptance; the place of doing and non-doing; of being in flow with the winds of FORTUNE.” – Corinne Chaves

“The author’s journey quickly becomes our own through this real-time deep dive into the mystery of Life’s unfolding. It’s tough to write much without feeling that you’re spoiling the ride for another reader, but the book welcomes us to join the author’s passionate search for wisdom, with all the vulnerability, curiosity, courage, and reflection that such a search requires. We meet famous and not so famous teachers, some of whom look a lot like house painters. By entering the author’s journey, we cannot help but reflect on and expand our own.” – L Wilder